General Upendra Dwivedi Takes Command As Chief Of The Army Staff

July 2, 2024

On 10 November 2017, at Varanasi, the late General Bipin Rawat and his wife Mrs Madhu Rawat had attended the bicentenary celebrations of 200 years of the first raising of a Gorkha unit of the 9th Gorkha Rifles.

This was one of the earliest units raised by the East India Company and had an ‘India-Nepal connect’.

However, the first regiment of these hardy Nepalese soldiers was actually raised by Sir Robert Colquhuon on 24 April 1815, in Uttaranchal with men from Nepal, Kumaon and Garhwal regions. At that time two battalions, 1/1 GR and 1/3 GR, were raised. To put it in perspective, the raising of these Gorkha units were preceded in the Indian Army by only a few others including the Madras and Grenadiers Regiments (1758), Punjab Regiment (1761), Rajputana Rifles (1775), Rajput Regiment (1778), Jat Regiment (1795) and Kumaon Regiment (1813).

The Gorkha soldiers recruited in the army could be described, The relationship between the Nepali Army and the Indian Army is cornerstone of otherwise excellent relations between these two countries. A large number of officers and men of the Nepal Army undergo professional military courses in India. not in any derogatory sense, as the Foreign Legion of India, for, although soldiers of our army, they are unexampled for their gallantry and loyalty. However, they are not citizens of India, but those of the adjoining Republic of Nepal.

Recruited under special treaties between India and Nepal, these wiry gallant broad-chested big-hearted men were first taken into the East India Company’s service towards the end of the Anglo-Nepal Wars in 1815 when parties of the captured enemy made over their allegiance to General Ochterlony after the surrender of the Nepalese chieftain Amar Singh and the fall of his fortress of Malaun. Four irregular Nepalese units were at first authorised; the first two to be known as the 1st and 2nd Nasiri Gurkha Battalions, the name ‘Nasiri’ implying friendly.

David Ochterlony and British political agent William Fraser were among the first to recognise the potential of these hardy Gurkha soldiers. During the war, the British used these defectors from the Gurkha Army and employed them as irregular forces. Fraser’s confidence in their loyalty was such that in April 1815, he proposed forming them into a battalion under Lt. Ross called the Nasiri Regiment. This regiment, which later became the 1st King George’s Own Gurkha Rifles, saw action at Malaun Fort under the leadership of Lt. Lawtie, who reported to Ochterlony that he “had the greatest reason to be satisfied with their exertions”.

About 5,000 men entered British service in 1815, most of whom were not just Gorkhalis, but Kumaonis, Garhwalis and other Himalayan hill men. These groups, eventually lumped together under the term Gurkha, became the backbone of British Indian forces especially for fighting in the jungles and mountains.

As well as Ochterlony’s Gurkha Battalions, Fraser and Lt. Frederick Young raised the Sirmoor Battalion, later to become the 2nd King Edward VII’s Own Gurkha Rifles. An additional battalion, the Kumaon was also raised, eventually becoming the 3rd Queen Alexandra’s Own Gurkha Rifles.

Gurkhas served as troops under contract to the British East India Company in the Pindaree War of 1817 (The Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1819) was the final and decisive conflict between the British East India Company (EIC) and the Maratha Empire), in Bharatpur in 1826, the First and Second Anglo-Sikh Wars in 1846 and 1848 along with a number of other battles that dotted that era.

During the first Indian War of Independence which started in 1857, these soldiers fought on the British side and became part of the British Indian Army on its formation. The 8th (Sirmoor) Local Battalion made a notable contribution during the conflict, and 25 Indian Order of Merit awards were made to men from that regiment during the Siege of Delhi.

Twelve regiments from the Nepalese Army also took part in the relief of Lucknow under the command of Shri Teen Maharaja Jung Bahadur Rana of Nepal and his older brother C-in-C Ranodip Singh Kunwar (Ranaudip Singh Bahadur Rana) (later to succeed Jung Bahadur and become Sri Teen Maharaja Ranodip Singh of Nepal).

After this war, the 60th Rifles pressed for the Sirmoor Battalion to become a rifle regiment. This honour was granted in 1858 when the battalion was renamed the Sirmoor Rifle Regiment and awarded a third colour. In 1863, Queen Victoria presented the regiment with the Queen’s Truncheon, as a replacement for the colours that rifle regiments do not usually have.

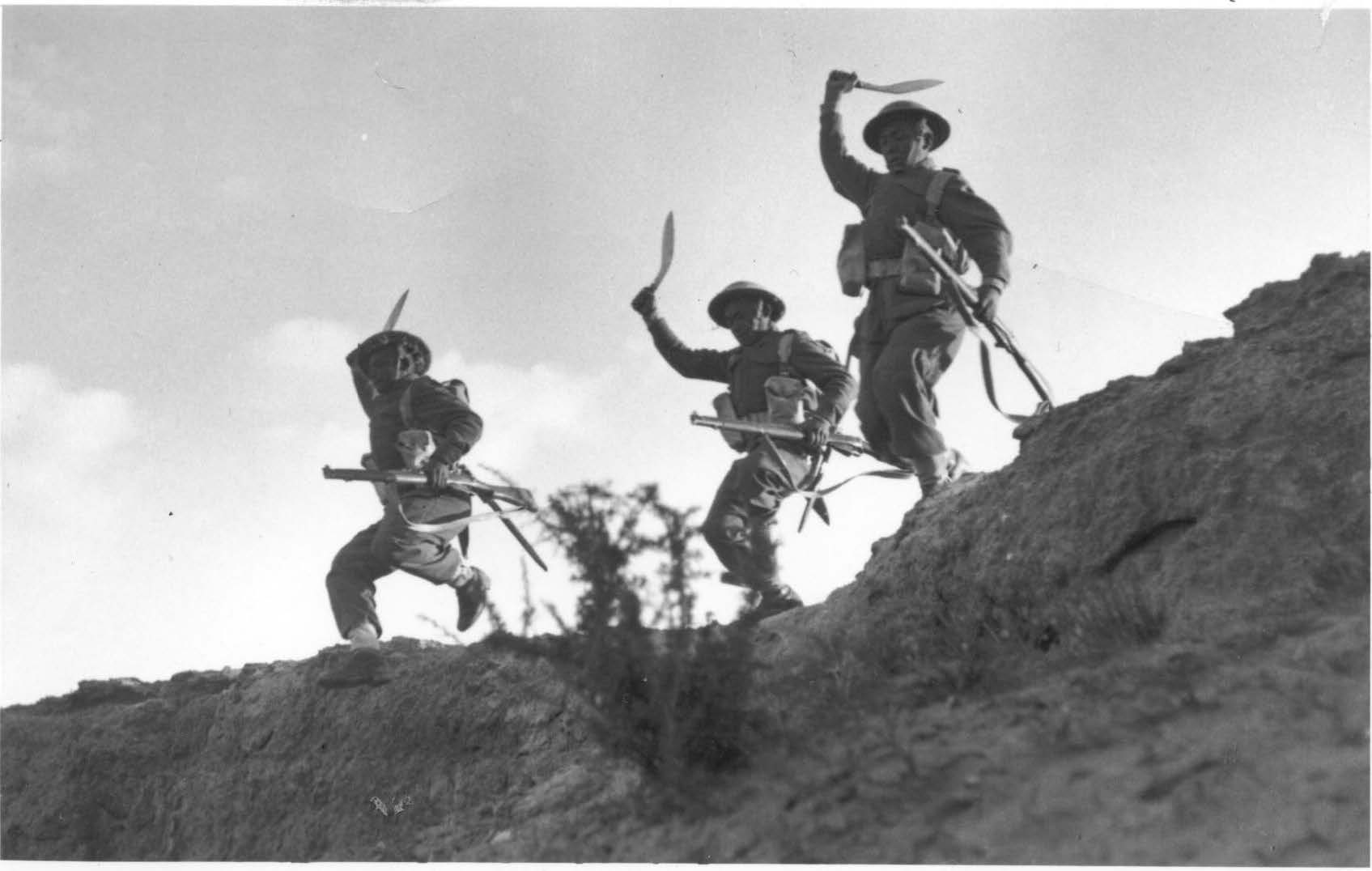

During World War I (1914–1918), more than 200,000 of these soldiers of Nepal served in the British Army, suffering approximately 20,000 casualties and receiving almost 2,000 gallantry awards. The number of Gurkha Battalions was increased to 33, and Gurkha units were placed at the disposal of the British High Command by the Nepalese government for service on all fronts. Further, along with these soldiers, many volunteers served in non-combatant roles, serving in units such as the Army Bearer Corps and the labour battalions.

A large number also served in combat in France, Turkey, Palestine, and Mesopotamia. They served on the battlefields of France in the battles of Loos, Givenchy, and Neuve Chapelle; in Belgium at the battle of Ypres; in Mesopotamia, Persia, Suez Canal and Palestine against Turkish advance, Gallipoli and Salonika. One detachment served with Lawrence of Arabia. During the Battle of Loos (June–December 1915), a battalion of the 8th Gurkhas fought to the last man, hurling themselves time after time against the weight of the German defences, and in the words of the Indian Corps Commander, Lt. Gen. Sir James Willcocks, “found its Valhalla”.

During the unsuccessful Gallipoli Campaign in 1915, the Gurkhas were among the first to arrive and the last to leave. The 1st/6th Gurkhas, having landed at Cape Helles, led the assault during the first major operation to take a Turkish high point, and in doing so captured a feature that later became known as “Gurkha Bluff”. At Sari Bair, they were the only troops in the whole campaign to reach and hold the crest line and look down on the straits, which was the ultimate objective. The 2nd Battalion of the 3rd Gurkha Rifles (2nd/3rd Gurkha Rifles) fought in the conquest of Baghdad.

Following the end of the war, the Gurkhas were returned to India, and during the inter-war years were largely kept away from the internal strife and urban conflicts of the sub-continent, instead being employed largely on the frontiers and in the hills where fiercely independent tribesmen were a constant source of trouble.

As such, between the World Wars the Gurkha Regiments fought in the Third Afghan War in 1919. The regiments then participated in numerous campaigns on the North-West Frontier, mainly in Waziristan, where they were employed as garrison troops defending the frontier. They kept the peace among the local populace and engaged with the lawless and often openly hostile Pathan tribesmen.

During this time the North-West Frontier was the scene of considerable political and civil unrest and troops stationed at Razmak, Bannu, and Wanna saw extensive action.

During World War II (1939–1945), there were ten Gurkha Regiments, with two battalions each, making a total of 20 pre-war battalions. Following the Dunkirk evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in 1940, the Nepalese government offered to increase recruitment to enlarge the number of Gurkha Battalions in British service to 35. This would eventually rise to 43 battalions.

A large number also served in combat in France, Turkey, Palestine, and Mesopotamia. They served on the battlefields of France in the battles of Loos, Givenchy, and Neuve Chapelle; in Belgium at the battle of Ypres; in Mesopotamia, Persia, Suez Canal and Palestine against Turkish advance, Gallipoli and Salonika. One detachment served with Lawrence of Arabia. During the Battle of Loos (June–December 1915), a battalion of the 8th Gurkhas fought to the last man, hurling themselves time after time against the weight of the German defences, and in the words of the Indian Corps Commander, Lt. Gen. Sir James Willcocks, “found its Valhalla”.

During the unsuccessful Gallipoli Campaign in 1915, the Gurkhas were among the first to arrive and the last to leave. The 1st/6th Gurkhas, having landed at Cape Helles, led the assault during the first major operation to take a Turkish high point, and in doing so captured a feature that later became known as “Gurkha Bluff”. At Sari Bair, they were the only troops in the whole campaign to reach and hold the crest line and look down on the straits, which was the ultimate objective. The 2nd Battalion of the 3rd Gurkha Rifles (2nd/3rd Gurkha Rifles) fought in the conquest of Baghdad.

Following the end of the war, the Gurkhas were returned to India, and during the inter-war years were largely kept away from the internal strife and urban conflicts of the sub-continent, instead being employed largely on the frontiersand in the hills where fiercely independent tribesmen were a constant source of trouble.

As such, between the World Wars the Gurkha Regiments fought in the Third Afghan War in 1919. The regiments then participated in numerous campaigns on the North-West Frontier, mainly in Waziristan, where they were employed as garrison troops defending the frontier. They kept the peace among the local populace and engaged with the lawless and often openly hostile Pathan tribesmen.

During this time the North-West Frontier was the scene of considerable political and civil unrest and troops stationed at Razmak, Bannu, and Wanna saw extensive action.

During World War II (1939–1945), there were ten Gurkha Regiments, with two battalions each, making a total of 20 pre-war battalions. Following the Dunkirk evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in 1940, the Nepalese government offered to increase recruitment to enlarge the number of Gurkha Battalions in British service to 35. This would eventually rise to 43 battalions.

A total of 2,50,280 Gurkhas served in 40 battalions, plus eight Nepalese Army battalions, parachute, training, garrison and porter units during the war, in almost all theatres. In addition to keeping peace in India, Gurkhas fought in Syria, North Africa, Italy, Greece and against the Japanese in the jungles of Burma, northeast India and also Singapore. They did so with distinction, earning 2,734 bravery awards in the process and suffering around 32,000 casualties in all theatres.

Tripartite Agreement

At the time of Independence in 1947, a tripartite Agreement between the United Kingdom, India and Nepal was signed concerning the rights of Gurkhas recruited in armed forces of United Kingdom and India. This agreement did not apply to Gurkhas serving in the Nepalese Army. Under this agreement, four Gurkha Regiments of British Army were to be transferred to British Army and six regiments were to be transferred to the Indian Army. Pakistan also made a bid for these surplus Gorkha Regiments, but they did not press their claim, and, of course, Nepal too did not give assent to that claim. Later post the 1962 conflict, China too claimed and requested Nepal for ‘Gurkha Soldiers’ to serve in the PLA, but Nepal once again, did not give assent.

India today has 39 Gorkha Battalions serving in seven Gorkha Regiments (1st, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 8th, 9th and a new regiment raised post 1947, the 11th). Britain, on the other hand, has amalgamated the four regiments that had joined them, namely the 2nd, 6th, 7th and the 10th, to just two regiments, 1 RGR and 2 RGR. Further, those soldiers transferred to the British Army were immediately deployed to other remaining British colonies, in Malaya and Singapore, where their presence was required used to quell the Malayan Insurgency and also to Singapore where they replaced a Sikh unit which reverted to the Indian Army on independence. Even today, these Gurkha units remain deployed in Brunei and Singapore.

As per this tripartite agreement, it was also decided that a referendum be held in all Gorkha units to

give every Gorkha soldier a choice for service either in the Indian or the British Army. Till 1947, since the British had debarred Indians from joining the officer cadre of Gorkha Regiments, and even when Gorkha soldiers from Gorkha Regiments got promoted to commissioned ranks, they were not accommodated in Gorkha Regiments. They were posted to different Indian Regiments. British officers fervently believed that, since the Gorkha soldiers had been serving only under them, and they had no contact with Indian officers, the result of the referendum among Gorkha soldiers was a foregone conclusion. But the results of the referendum came as a rude shock to them and well over 90 per cent of the Gorkha soldiers who were to be transferred to the British Army, opted for service with the Indian Army. “Non-optees” from Gorkha Regiments earmarked for service with the British Army were immediately drafted into a newly raised 11th Gorkha Regiment of the Indian Army.

Amalgamation Into The Indian Army

During the initial months of the 1947-48 War in Jammu and Kashmir, there was no participation of Gorkha units. However, later, they more than made up for it in Kashmir. The Gorkhas distinguished themselves in the assault on 10,000 feet Pir Kanthi Hill and in the epic battle of Zojila. During the advance to Kargil, Subedar Harka Bahadur Gurung swam across an icy cold swift flowing river in winter to enable a rope bridge to be built. Even today, a concrete bridge later built at that site bears his name. There were many gallantry awards of Maha Vir Chakras and Vir Chakras earned by Gorkha units in Kashmir. They also earned an Ashok Chakra, the highest gallantry award during peace during the Police Action in Hyderabad.

In every war fought by the Indian Army post-Independence, the Gorkhas have played a gallant role. They have earned several Param Vir Chakras, the highest award for gallantry.

Excellent Defence Relations

Since 1965, both the countriesstarted the tradition of conferringthe title of an ‘honorary general’to each other’s army chief. Thetwo armies had been exchanginggoodwill visits since 1950, when thethen Indian Army Chief, General K.M. Cariappa (later Field Marshal),visited Nepal. Since then, 21 IndianArmy chiefs visited Nepal, while16 Nepali Army chiefs have visitedIndia during the same period.

The relationship between the Nepali Army and the Indian Army is cornerstone of otherwise excellent relations between these two countries. A large number of officers and men of the Nepal Army undergo professional military courses in India. Further, a large number also have close relations (both serving and retired) with their kith and kin who serve or have served in the Indian Army.

Traditionally, the Chief of the Army Staff of the Nepali Army visits India at the earliest after assumption of the post, during which he is conferred with the rank of an ‘Honorary General’ of the Indian Army by the President of India. In 2016, the Nepali Army Chief, General Rajendra Chettri, visited India and was conferred with the rank of ‘Honorary General’ in the Indian Army and the Indian Army Chief, General Bipin Rawat was conferred this rank in the Nepali Army in 2017. General Manoj Narawane visited Nepal in November 2020.

In 1995, India had in principle accepted the request of the Government of Nepal to assist the Nepali Army in its “Modernisation and Reorganisation” process. During 2004-2007, defence stores were provided to the Nepali Army gratis. Apart from the stores supplied under ‘Modernisation Programme’, Nepali Army also purchased defence stores on payment.

Due to the recent political changes in Nepal, the quantum of supply of defence stores supplied to the Nepali Army has considerably reduced.

Based on an agreement during the seventh Nepal-India Bilateral Consultative Group on Security, the two countries commenced joint training at platoon level of 30 men each in 2011. The first two joint exercises focused primarily on jungle warfare and counter-insurgency operations.

Troops shared their experiences and exhibited skill sets during joint training at Counter-Insurgency and Jungle Warfare School at Vairangate in Mizoram, and a similar school at Amlekhganj in Nepal. This joint training was upgraded to a company level in 2012.

Subsequently, Indian and Nepali armies crossed another historic milestone, when a battalion from each of the countries took part in a combined training programme to ensure inter-operability in the disaster-prone region of Uttarakhand.

The Indo-Nepali Joint Military Training Exercise Surya Kiran-V was conducted at Pithoragarh in Uttarakhand from 23 September to 06 October 2013. This was the first of the battalion-level combined training exercises between the two countries, and at least 400 soldiers from each army participated at Pithoragarh, where the focus was on ‘Disaster Response’ in the geological disaster-prone zones of the Himalayas.

In February 2016, the Ninth Indo-Nepali Combined Battalion Level Military Training Exercise Surya Kiran was conducted at Pithoragarh. During this exercise, the Indian Army and the Nepali Army trained together and shared their experiences of counter-terrorism operations and jungle warfare in mountain terrain.

These Surya Kiran series of exercises are bi-annual events, which are conducted alternatively in Nepal and India. The aim of these combined training exercises is to enhance interoperability between the Indian and the Nepali Army units.

The training focused on Humanitarian Aid and Disaster Relief including medical and aviation support. Both the armies stand to benefit mutually from these shared experiences, and this combined training, mutual interaction and sharing of experiences between both the countries further invigorates the continuing historical military and strategic ties, giving further fillip to the bilateral relations and existing strong bonding between both countries.