Navigating the Maritime Turn in Military Integration

Theatre commands are integrated military formations where all branches of the armed services—Army, Navy, Air Force, Space, and Cyber—within a geographic region are unified under one operational command. Traditionally land-centric, this format is now being extended to the seas, prompted by the evolving nature of threats.

The origins of maritime-centric theatre commands (MTCs) can be traced back to World War II, when Allied powers organized fleet commands with integrated air and logistics support across vast oceanic theatres. The U.S. Pacific Fleet and the British Eastern Fleet were among the earliest examples. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union’s Northern and Pacific Fleets operated with support from centralized ministries for space and cyber intelligence, resembling the modern coordination model seen in China’s Strategic Support Force (SSF).

In the post–Cold War era, the U.S. operationalized theatre-level maritime doctrine through Unified Combatant Commands like USPACOM (now USINDOPACOM), integrating space and cyber assets. These evolutions demonstrate how the nature of maritime threats—both state-based and asymmetric—has long dictated command structures. Modern MTCs inherit this layered complexity, operating in increasingly congested, contested, and connected waters.

The Indo-Pacific—home to over 60% of the global population and accounting for about 44% of international trade (Chaturvedi, 2022)—has emerged as a focal region where MTCs offer a crucial structural adaptation. They consolidate multi-domain capabilities, enable rapid decision-making, and provide deterrent resilience. This article examines MTCs within the broader Indo-Pacific security architecture, analyzes case studies of regional powers, identifies structural and strategic gaps and presents forward-looking policy recommendations.

Cross-Domain Convergence and Strategic Infrastructure

Contemporary security challenges in the Indo-Pacific increasingly transcend traditional naval warfare. These days, both state and non-state actors use electronic interference, grey-zone strategies, and cyber disruption to erode regional stability and restrict freedom of movement. Reports of GPS signal disruption near Taiwan and the South China Sea have raised concerns over the growing use of electronic warfare in contested maritime spaces, though several such events have been linked to non-hostile activities such as civilian signal calibration (Breaking Defense, 2024). Similarly, India remains one of the most cyber-targeted nations in the Indo-Pacific, reportedly experiencing over 2,000 attempted cyber incidents per organization each week, including attempts directed at maritime and naval digital infrastructure. These evolving threat vectors highlight the urgent need for deeper convergence between cyber, space, and maritime command structures.

USINDOPACOM has institutionalized this integration by combining space surveillance, AI-driven ISR, and autonomous maritime platforms. U.S. Navy’s Project. Conversely, China’s theatre commands—Northern, Eastern, and Southern—leverage centralized space and cyber capabilities through the PLA’s SSF, providing enhanced domain awareness beyond traditional sonar or radar systems.

Japan’s FY2022 defense budget stood at approximately ¥5.86 trillion (~$50 billion), with a significant portion allocated to bolstering maritime surveillance and submarine detection capabilities. ISR drones and coast guard coordination hubs now operate out of bases like Yonaguni and Amami Oshima to counter threats in the East China Sea.

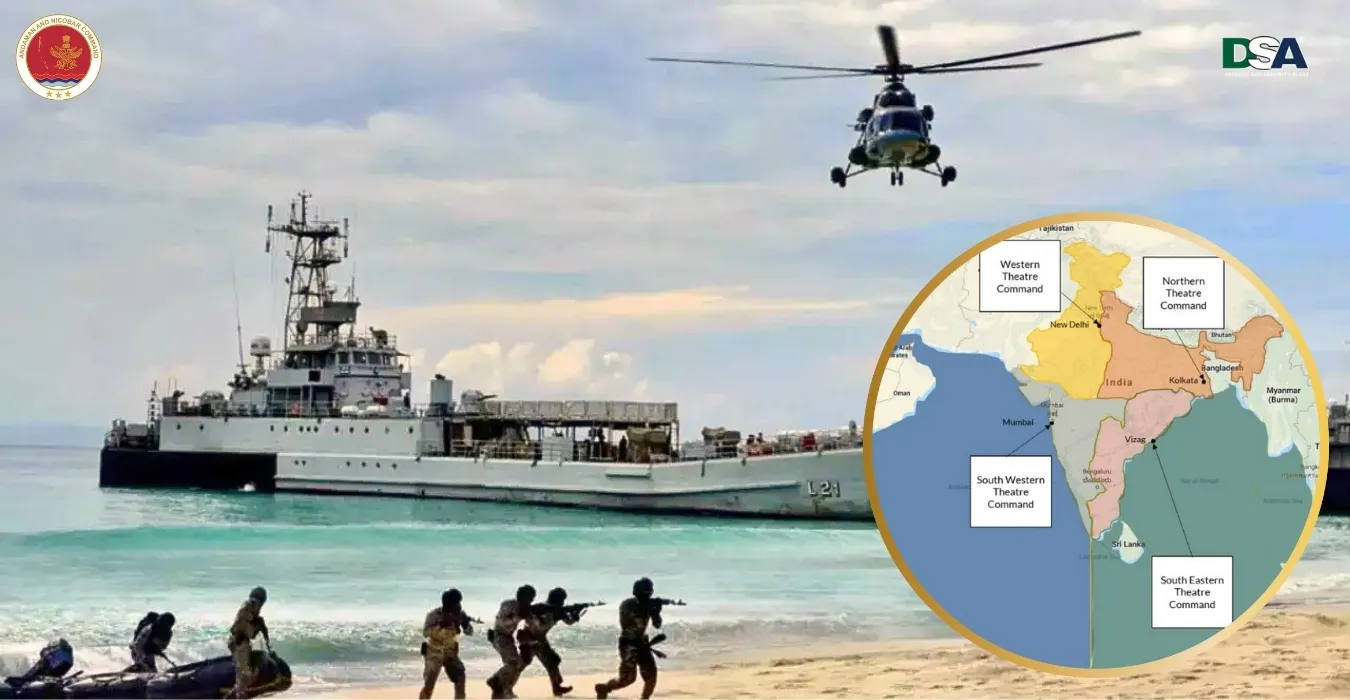

India’s envisioned MTC seeks to mirror this synergy but remains conceptually transitional. Interoperability challenges persist, especially between naval and air assets in the Andaman & Nicobar Command. Despite its strategic location near critical sea lanes, the Andaman & Nicobar Command (ANC) remains underutilized. Its infrastructure is outdated, real-time surveillance capacity remains weak, and its command authority is diluted by service-specific hierarchies. Without significant investment in command autonomy and ISR capabilities, ANC cannot serve as the operational testbed for India’s maritime theatre visionIndia lacks a real-time data fusion structure comparable to the United States’ Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2), restricting operational responsiveness.

Furthermore, India’s doctrinal framework has not fully kept pace with structural reformThe 2017 Joint Armed Forces Doctrine remains advisory, with no legal enforcement across services.. Currently, theatre commanders derive operational authority from their respective service headquarters, not from a unified statutory mandate—creating ambiguity during crises. Without a comprehensive Theatre Command Doctrine Bill, questions remain over authority distribution during peacetime and wartime. While India’s Defence Cyber and Space Agencies are conceptually integrated into MTC planning, they are yet to be fully embedded in the operational command structure.

Regional Trends and Capability Evolution

Across the Indo-Pacific, states are modifying their command arrangements to overcome littoral vulnerabilities and external coercion. The Philippines initiated a “One-Theatre” command in 2025 in response to heightened Chinese aggression at Scarborough Shoal (Reuters, 2025). Singapore’s Maritime Security Task Force (MSTF), which integrates naval, coast guard, and customs agencies, intercepted 28 unauthorized maritime entries in 2023, validating real-time civil-military integration (Singapore Ministry of Defence, 2024).

France’s ALPACI command, based in New Caledonia, operates as a joint maritime task force and collaborates with India under the Franc-India logistics pact. It has become central to the EU’s naval presence in the Indo-Pacific, participating in multilateral patrols across the Southern Indian Ocean. Australia’s 2023 Defence Strategic Review prioritized integrated deterrence and reconfigured command elements to enable faster maritime deployments in the Northern Approaches. Exercises such as Talisman Sabre now simulate full-spectrum joint operations, including AI and cyber coordination.

MTCs increasingly address non-traditional security roles—HADR, anti-piracy, and IUU fishing. The Indian Navy’s response to Cyclone Biparjoy (2023) showcased effective MTC-style collaboration with civilian agencies. Similarly, Singapore’s MSTF used a hybrid command to intercept Chinese distant-water fishing (DWF) vessels entering Indonesian waters.. Similarly, Singapore’s MSTF employed a hybrid command to intercept Chinese distant-water fishing (DWF) fleets intruding into Indonesian waters. However, ASEAN’s role in supporting regional maritime command integration remains constrained by internal divergences. Countries like Vietnam and the Philippines advocate assertive postures, while others, such as Cambodia and Laos, lean toward accommodation with China. This lack of consensus prevents the formation of a unified ASEAN maritime doctrine or response mechanism. Until institutional cohesion improves, ASEAN’s maritime contribution will remain reactive and fragmented, limiting its ability to participate in cohesive MTC frameworks. These examples underscore MTCs’ peacetime relevance in securing the maritime commons.

The 2022 Tonga volcanic eruption response—featuring joint HADR deployments by Australia, the U.S., and Japan-further illustrated the operational value of integrated naval-airlift task forces during humanitarian crises.

Comparative Overview: MTC Capabilities in the Indo-Pacific

India emerges as the most prominent case of unrealized potential, where the lack of a shared digital architecture and standardized doctrine inhibits interoperability. The proposed MTC headquarters at Karwar remains non-operational, and joint logistics across commands remain under-resourced (MoD, 2023).

MTCs derive deterrence from sustained force projection. This requires robust logistics, forward-operating bases, and prepositioned supplies. China’s dual-use ports in Djibouti, Gwadar, and Hambantota extend PLA Navy’s operational reach into the Indian Ocean. In contrast, India has logistics agreements with Japan, France, and Australia, allowing naval access to Djibouti, Nouméa, and Réunion Island. India-supported regional systems such as Sri Lanka’s Colombo-based Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) and the Maldives’ Coastal Surveillance Radar System (CSRS) reflect growing efforts toward a connected regional maritime surveillance framework

Policy Recommendations

- Accelerate AI Integration: Develop indigenous AI-powered C2 systems to support seamless sensor-to-shooter networks.

- Institutionalize Joint Training: Conduct quarterly inter-service exercises, modeled after U.S. RED FLAG and Pacific Sentry operations.

- Legislate Theatre Command Doctrine: Pass a binding bill granting legal primacy to theatre commanders in crisis scenarios.

- Enhance Civil-Military Coordination: Form joint civilian-military planning cells within MTCs to ensure synchronized HADR and hybrid threat responses.

While greater integration is essential, excessive centralization risks blunting service-specific strengths. An overly rigid theatre command may suffer from bureaucratic lag during time-sensitive operations. A hybrid framework—where centralized oversight coexists with service-level tactical flexibility—may offer a more adaptive and mission-responsive structure, especially in diverse democracies like India.

Forecasting the Future Indo-Pacific Theatre Command Architecture

- Incremental Integration (60%): Most regional powers fully operationalize MTCs by 2030. India’s MTC becomes functional, ASEAN launches a maritime fusion center, and theatre-level exercises become regular.

- Crisis-Driven Acceleration (30%): A flashpoint, such as a Taiwan blockade, fast-tracks integration. Bureaucratic inertia is sidestepped, and joint ISR-sharing protocols are activated.

- Strategic Drift (10%): Economic or political disruptions stall integration. Defence budgets plateau. China fills the void through an assertive posture.

Current fiscal trends favor the incremental integration scenario. India allocated ₹47,515 crore (~$5.7 billion) to naval modernization in FY2023–24, accounting for nearly 48% of the Navy’s total budget that year (MoD Annual Report, 2023). Japan’s FY2024 defence budget of $51 billion earmarks 20% for maritime command and submarine detection infrastructure. Meanwhile, Indian-supported platforms such as Sri Lanka’s Colombo-based MRCC and the Maldives’ Coastal Surveillance Radar System (CSRS) indicate the emergence of a regionally networked MTC-supportive infrastructure.

Conclusion

Maritime-centric theatre commands are reshaping the Indo-Pacific security landscape. By integrating cyber, space, AI, and kinetic capabilities, MTCs offer a resilient, responsive, and interoperable force structure suitable for 21st-century threats. While the U.S. and China lead operationally, countries like India, the Philippines, and Singapore are adapting at varying speeds. For MTCs to reach full potential, structural bottlenecks—especially doctrinal gaps and inter-service friction—must be overcome through legislation, fiscal commitment, and technological innovation. In a region defined by contested waters and grey-zone competition may well shape whether the Indo-Pacific remains a cooperative maritime commons or fragments into zones of persistent contestation and coercive control.

References

- Anwar, D. (2024). ASEAN Centrality. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364508837

- Chaturvedi, S. (2022). Introduction: Indianoceanness and its Indo-Pacific dimensions. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 18(3), 205–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/19480881.2023.2231704

- Menon, L. G. D. P. (2021). India’s Theatre Command System: A Proposal. Takshashila Institution. https://takshashila.org.in/s/India-Theatre-Command-System-Prakash-Menon-Mar21-Takshashila.pdf

- Narvenkar, M. V. (2025). Geopolitical Shifts in the Indo-Pacific: China’s Ambitions and India’s Security Concerns. Jadavpur Journal of International Relations, 09735984251347797.

- Pandalai, S. (2022). The Indo-Pacific consensus: The past, present and future of India’s vision for the region. India Quarterly, 78(2), 189-209. https://doi.org/10.1177/09749284221090717

- Peron-Doise, M. (2025). Indo-Pacific’s Vision of France and India: Enhancing Maritime Multilateralism. In The Routledge Handbook of Maritime India (pp. 122-135). Routledge India. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781003607434-11

- Reuters. (2025, June 30). Philippines says military leaders working to set-up ‘one-theatre’ approach in East, South China seas. https://www.reuters.com

- Shin, D. (2024). Practical Understanding of U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy: Analysis of USINDOPACOM. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus.

- SIPRI. (2024). Navigating Security Dilemmas in Indo-Pacific Waters. https://www.sipri.org

- Sullivan de Estrada, K. (2023). India and order transition in the Indo-Pacific: Resisting the Quad as a ‘security community.’ The Pacific Review, 36(2), 378–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2022.2160792

- Technology Magazine. (2025). US Indo-Pacific Command invests in tech transformation. https://www.technologymagazine.com