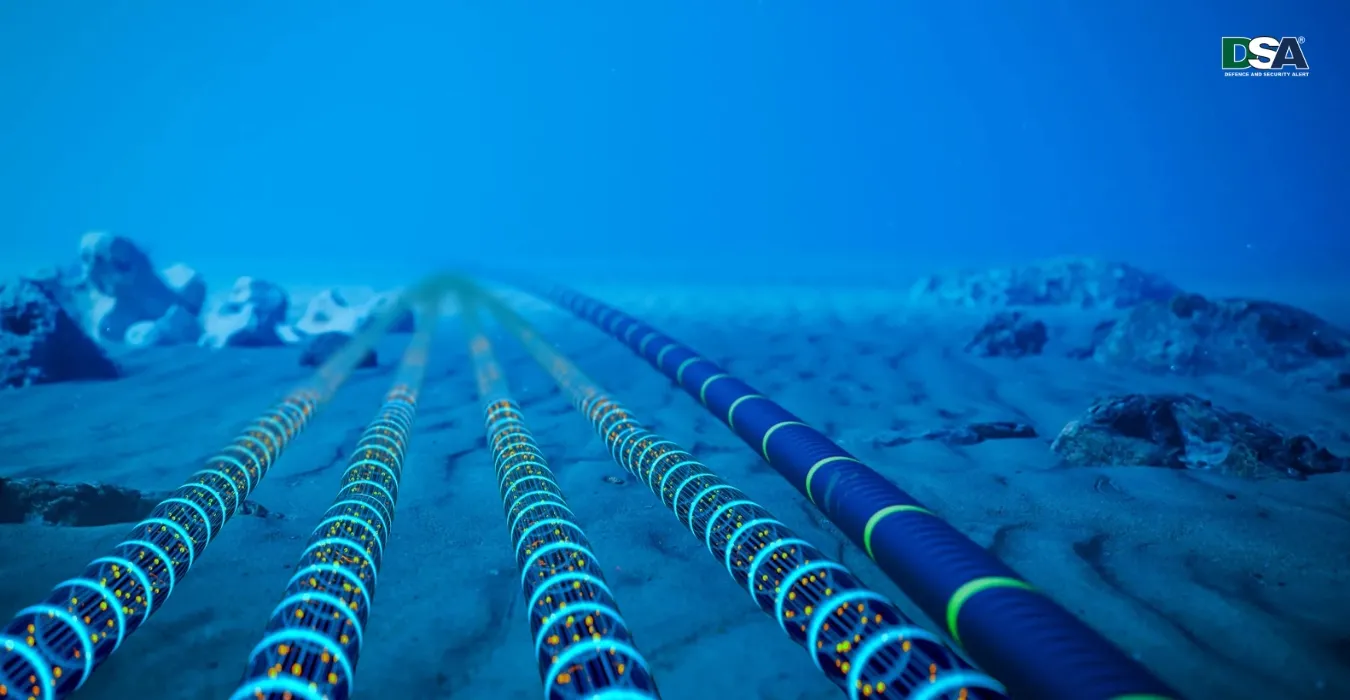

Submarine cables, also known as undersea cables, are fibre optic cables laid on the ocean floor. These cables are laid using special cable layer ships. They form the backbone of the modern internet, carrying over 95% of all international data traffic, including emails, financial transactions, video calls, and sensitive government communications. Despite the prominence of satellites in the popular imagination, it isthese deep-sea fibre optic cables, laid across the oceans and seas, that enable real-time, high-capacity digital connectivity.

The History of the Submarine Cables

The story of submarine cables goes back to the mid-1800s when people first started thinking about sending messages through wires under the sea. The very first submarine cable was laid in 1850 between Dover in England and Calais in France, across the English Channel. The cable was short, only about 20 miles, and it did not work for long. However, in 1851, a new cable was successfully laid on the same route. This marked the beginning of international undersea communication. The cable was made of copper wire to carry signals and a special tree sap called gutta-percha to protect it from seawater.

The Second Attempt

In 1854, American businessman Cyrus Field proposed laying a cable across the Atlantic Ocean from Ireland to Newfoundland. After several failed attempts, the first successful cable was completed in 1866 by the ship Great Eastern, which also recovered an earlier lost cable, creating two working connections between Europe and North America.

These early achievements laid the foundation for a global undersea cable network by the late 1800s. Though technology has advanced, modern cables are still laid under the sea and continue to carry most of the world’s communication traffic.

In the 1800s, submarine cables were only capable of carrying basic telegraph messages using Morse code, with transmission speeds as low as 1 to 2 words per minute. Even with improvements by the end of the 19th century, data rates remained extremely limited, just a few bits per second. These cables were mainly used for short, urgent messages between governments and businesses. On the other hand, modern fibre optic cables have the ability to transmit multiple terabits of data per second. For example, the MAREA cable, which is a joint project of Microsoft, Facebook, and Telxius, spans the Atlantic Ocean and has a capacity of up to 200 terabits per second. Through these cables, we are able to communicate worldwide faster and transfer vast amounts of data, including video streaming, online banking, and military communications. The unseen infrastructure that underpins all international digital communication is submarine cables. The difference in capacity between the 1800s and today is millions of times, showcasing the remarkable development of undersea cables.

Strategic Assets in the Digital Era

Submarine cables are now considered a strategic asset in international politics rather than merely a piece of technical infrastructure. Concerns about influence, security, and monitoring have increased as nations compete for control of these crucial data channels. The competition is particularly apparent in the Indo-Pacific, where digital infrastructure is forming new power dynamics.

Source: The Brilliant Submarine Cable Map – Brilliant Maps

China’s Cable Diplomacy

China, through its Digital Silk Road initiative launched in 2015, aims to corner as much as 60% of the global market for submarine cables. This expansion is not only business but is increasingly regarded as a component of a wider plan to redefine digital global governance, shape data flows, and potentially exploit geopolitical vulnerabilities.

China’s rapid ascension in the global submarine cable industry is driven by state-subsidized entities such as HMN Technologies (formerly Huawei Marine Networks), Hengtong Marine, SB Submarine Systems (SBSS), and Fiber Home. HMN Technologies alone has put in nearly 18% of the cables installed globally over the past four years and constructed or maintained almost a quarter of today’s cables in the world. China has built or funded cable landing stations in more than 20 countries, including Pakistan (Gwadar and Karachi), Djibouti, Kenya, Cameroon, France and Malta.

Projects like the PEACE cable (Pakistan and East Africa Connecting Europe) reflect China’s ambitions to construct data highways that bypass traditional Western-aligned routes. The 15,000 km cable links China with Africa and Europe across the Indian Ocean, going out of its way to skip Indian jurisdiction and key chokepoints like the Malacca Strait. China is using a model of offering low-cost, rapid-deployment, turnkey cable systems to rising countries, probably where Western firms face regulatory, financial, or political challenges.

Concerns Over Espionage and Dual-Use Risks

Many Chinese companies involved in laying and maintaining undersea cables are either owned by the government or closely supported by it. This creates concern because, although these cables are used for normal internet and communication purposes, they could also be used for military spying. Experts from the West are worried that Chinese companies might hide tools inside the cables that can secretly watch or change the information being sent.

There are also worries about how these Chinese cable ships operate. For example, some ships, like those from the SBSS, have been seen turning off GPS tracking while working on cables. This makes it difficult to know what they are doing and raises fears that they could install hidden equipment or collect secret data. A research group called CNAS has warned that in times of conflict, the Chinese military might use these cables to cut off communications or launch cyber-attacks.

In recent years, there have been incidents that support these concerns. In early 2023, two undersea cables near Taiwan’s Matsu Islands were cut, leaving the area without internet for about 50 days. Chinese ships nearby were suspected. Later, more cables were damaged near Taiwan’s capital and other islands. In response, Taiwan’s government has listed nearly 100 ships as suspicious, most of them linked to China or registered under different country flags.

These incidents are part of a disturbing trend:

In October 2023, the Balticconnector pipeline and two telecom cables were damaged near the Baltic Sea. European suspicion fell on the New Polar Bear, a Chinese-owned ship. China admitted involvement months later, but many experts still suspect intentional sabotage. This echoes alleged Chinese collaboration with Russian maritime activities targeting critical European infrastructure.

Global Reactions and Strategic Countermoves

China’s ambitions go beyond Asia and Africa. In Latin America, Beijing has been interested in connecting the region to China via a South America-Asia cable. While Chile partnered with Google in the Humboldt cable project, China’s growing presence in Peru (Chancay Port) could result in China establishing its own cable routes and more integration of Chinese infrastructure in the Western Hemisphere.

In the Middle East and North Africa, the Atlantic Council states China’s cable footprint as a master plan of strategy to control global information flows. With the holding of strategic infrastructure, China can manipulate digital behaviour, steal confidential information, or hold sway over regional management of the internet.

China has also developed previously imported advanced ROVs, ploughs, and cable-laying equipment. These systems are now used worldwide, from Malaysia and the Philippines to Kenya and Chile. The Industry and Planning Research Institute of the CAICT confirms that China now has a complete supply chain for submarine cable manufacturing, laying, and maintenance—placing it on par with global leaders like SubCom (USA), ASN (France), and NEC (Japan).

Chinese Hidden Agenda

China’s increasing involvement in the underwater cable sector has elicited varying responses from nations worldwide. Some Western countries have made the decision to prevent Chinese businesses from participating in significant projects. They are concerned that China may sabotage or spy on them using these cables. China, on the other hand, claims to abide by international regulations and merely provides a less expensive option in a market that was previously dominated by Western businesses.

According to the International Cable Protection Committee (ICPC), over 200 issues with underwater cables occur annually. About 80% of them are brought on by human activity, such as ship anchors or fishing boats. However, some experts believe these may not be mere coincidences because Chinese ships continue to appear in sensitive areas, such as the Baltic Sea and the vicinity of Taiwan. Rather, they might be a component of a larger plan to interfere with communications in strategic areas covertly.

Hybrid Threats and New Dangers

Submarine cables used to be seen as just part of technical infrastructure, but now they are becoming a new kind of target in modern conflict. These cables can easily be physically damaged by submarines, underwater drones, or even fishing boats pulling anchors. In some cases, attackers can secretly tap into them to spy on sensitive data. Cyberattacks are another danger; hackers can target cable landing stations and nearby data centres to disrupt or steal sensitive information.

If these cables are damaged during a conflict, it can lead to major problems like delays in military communication, financial disruptions, and loss of access to vital services. This is not just a theory; Russian submarines have been seen lurking near NATO’s undersea infrastructure, and Chinese ships have been blamed for cutting cables near Taiwan and in the Baltic Sea. These incidents show that submarine cables are now part of global power struggles.

India’s Strategic and Technical Vulnerabilities

India depends heavily on submarine cables; most of them are built and managed by foreign companies. Key cable landing points like those in Mumbai and Chennai are vital. If one is damaged, it could lead to internet blackouts across the country. India also does not have enough backup routes or repair capacity. There is a lack of local expertise and tools to build, fix, or monitor these cables. This puts India in a risky position if tensions rise.

Global Competition

China’s growing control over digital infrastructure is raising alarms. Countries like the U.S., Japan, and Australia now see these cables as critical to national safety. Australia has blocked Huawei from some projects. The U.S. and Japan are working to build more secure networks. The QUAD group (India, U.S., Japan and Australia) has started building trusted cable routes together. If India plays an active role, it can protect its own cables and boost its digital strength globally.

What Can India Do?

India needs a clear and strong action plan to deal with the rising threats to submarine cables. First, it should create a national strategy focused on protecting these cables, with a special body that brings together experts from defence, telecom, intelligence, and foreign policy. India should also build its own capabilities by investing in locally owned cables, landing stations, and repair ships. This effort can include partnerships with private companies and support from DRDO and ISRO to develop tools for underwater surveillance and fast repairs. In addition, India must work closely with trusted countries, especially the Quad members, to build safe cable routes and avoid reliance on rival Powers. At sea, the Navy and Coast Guard should be trained and equipped to monitor undersea cables and respond quickly to threats. Advanced technologies like artificial intelligence can help detect cable damage early and track suspicious activity on the seabed. These steps will help secure India’s digital lifelines and protect national security.